As communication professionals we all know what work goes into building a sticky brand and the value attached to it. Rarely, however, do we give ample credence to our own brands; this deserves especial attention in today’s digital market place.

As noted on the Knowledge@Wharton blog, in a prescient move the Vatican set up a Twitter account for Pope Benedict XVI (the first Pope to tweet) under the guise of “@Pontifex”. Because Pope Benedict’s name was not associated with the twitter account, ownership of the posts and associated reputation is clearly established: the account refers to the person of the pope, and not the pope himself. Benedict will not have access to this account, and it is likely that Francis will resume where Benedict left off. The Vatican has set a markedly insightful precedent that all marketing communication managers should take note of.

Noah Kravitz was sued for taking his 17,00 Twitter followers with him when he left his previous employer.

But why is this important? In the aforementioned blog post the author highlighted a legal case in which a company settled a lawsuit against a former employee who used Twitter followers the company believed it owned for his own gain. Just in case the story has faded from memory (it made national headlines), essentially what happened was the employee maintained a Twitter account associated with both his name and the company, when he left he changed it to just his name. He then started working at a competitor and used the followers he acquired while at his ex-employer to build his new employer’s reputation The previous employer’s argument was ownership of the 17K+ followers. This begs the question, did the employee really steal the followers?

This question is still largely undecided. The case was settled privately so no legal precedent was set leaving communication professionals holding their breath indefinitely. An interviewee cited in the Wharton blog, Janice Bellace, professor of legal studies and business ethics at Wharton, claims the best we can do to resolve the question of ownership for the time being is reference back to before social media. Her explanation is that it may be illegal to walk out of the office with a filing cabinet (or hard disk) with a client list on it, but writing down contact information in a notebook (or saving it to your phone) over the course of five years of tenure at the company most likely is not illegal.

The article continues to point out that in all reality followers probably can’t be “owned”. Unfortunately the article did not delve into why this is, but the impression given is that nothing legally binding happens between followers and an online personality. The article closes with a recommendation to set up policy and agreements such that there is an internal precedent established regarding social media accounts.

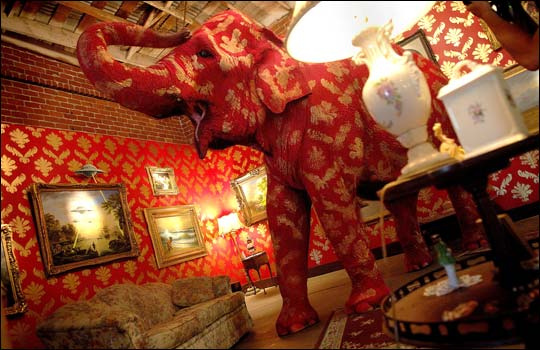

But I think there is an elephant hiding in the room: who owns you. (For anyone wondering I do believe that elephants can hide in a room. Not in the sense that it is doing so intentionally, of course, because they are ridiculously large, preposterous creatures and not noticing one takes some level of cognitive effort. Elephants hide in rooms through disavowal in the Lacanian sense. “Sure I know there is an elephant in the room, what do you think I am, an idiot? I just refuse to acknowledge its presence in respect of my own psychological comfort.” I digress though…) Who owns you, your personal, digital brand? Online participation in social media is an extension of the individual. Features like Google authorship help build this personal brand as content, images, and other information is pushed live online. An organization may not gain huge sums of money through their association with my blogging or other published content, but they could, and what is my right to that value creation? If I leave my current employer do they own both the content I produced and published online as well as my associated reputation? If I leave should it be disassociated from my personal brand?

Much like the Twitter case we can turn to print media for an answer: when something was published in print, a newspaper or magazine for example, generally you could not retract the article. Once you said something supporting or building your employer’s reputation it was more or less set in stone. That being said, it also did not stick with you in the same way. Personal brands were not a reality. How many people in the 1980’s went to libraries to track down everything that Ivan Boesky published? Certainly not near as many as familiarized themselves with John Thain from Merrill Lynch a few years back. The digital era has made our personal brands sticky in the sense that they are always out there.

When I first authored this post I was inclined to conclude with this neuter claim, “I am not certain where I stand on this yet, however I believe that it is a conversation professionals need to start. At first blush, and maybe it is my rural upbringing, I am inclined to say that I own me and my brand – not the company I work for. When I leave it should leave with me. The thought of somebody continuing to profit off of my name after I have moved on seems inherently wrong. I have been wrong before, and may be wrong this time as well. What are your thoughts?” An insightful reviewer suggested that if I really want engagement around this I should take a stance – at the very least lean stronger towards one. I went out for a run, plugged in some Stravinsky, and thought long and hard about where I stand on this one.

So here it is. I am radically contingent. If I existentially go away nothing replaces me – at least that is what I believe; I am indeed a beautiful and unique snowflake (my ego needs this belief.) This radical contingency is not extended to my occupation, however. If I go away someone, or even something, may replace me, meaning that in this instance I am superficially contingent (kind of a jagged pill to swallow, but it’s reality.) Previously personal brands were radically contingent on the persistence of the individual at an organization as it was hard for companies to benefit from the reputation, influence, or brand of a person if he left the company. Personal brands, however, have become superficially contingent in regards to the individual – they can exist sans individual presence. I see this as one of the fundamental flaws in postmodern reality. While we strive to disassociate the signifier from the signified thus liberating the individual to own his frame of reference in regards to interpreting signifiers generally, we hypocritically oppose allowing the same hermeneutic violence’s application to ourselves. Hypocritical as it may be, I still believe that I should have some say in the image that is Nik – particularly how it is understood and profited from. Disallowing me this right is a violence in the realist sense. It strips me of my personal freedom regarding meaning and value creation. Granted I may forfeit some of this freedom given certain actions, like signing a document allowing a company to perpetuate association with my brand post departure, I nevertheless believe that personal brand ownership is real, and in regards to leaving an employer it should be at the discretion of the brand owner if that organization can continue to profit from his personal brand.

3 Responses to Who Owns You?