Ah, the elusive success of the guerrilla marketing campaign… That tricky little green fairy chased by nouveau-marketing firms and cutting edge ad agencies. As Jay Conrad Levison, coiner of the actual phrase defines it, the art of “achieving conventional goals, such as profits and joy, with unconventional methods, such as investing energy instead of money.” If you are successful, your brand has likely achieved the ultimate grand-prize. Coolness. If you fail, well, you and yours are likely to go down in (very stylish) flames.

The reason it is so difficult to pull of a successful stealth campaign, perhaps, is because the modern roots of guerrilla marketing (not the original concept, but the contemporary re-envisioning of its design and feel) don’t come from the corporate world. They come from art.

Take, for example, one of the earliest guerrilla marketing campaigns of my recollection—Obey. Shepard Fairey, the artist who later went on to design and distribute Obama’s iconic, campaign winning Hope portrait, peppered the streets and subways of New York with a highly stylized, mysterious image of Andre the Giant. The images, which generally took one of two forms (see below), followed to daredevil placement tactics of renowned street artists Banksy and Invader. These artists stage a type of visual urban invasion, placing stickers, murals and posters in highly visible, hard to reach, and absolutely illegal places.

The purpose of the Obey campaign, however, was not simply that of an act of art. Fairey intended the Obey images to call attention to the ethically fuzzy practice of guerrilla marketing and stealth ambient advertisements. Along the way, Obey’s rebellious social parody, became a phenomenon in and of itself. By the early 1990s, tens of thousands of Obey images were plastered around urban centers around the globe. Fairey’s unruly anti-advertising stunt became synonymous with a cool, damn-the-man subculture.

And then of course, irony of ironies, Obey went on to become an enormously lucrative line of clothing and merchandise. How convenient that the branding and advertising had already been so well established.

Fairey’s work inadvertently set the standard in guerrilla marketing, to be used to sell real flesh and blood products, but riding on the winds of what at least appears to be a grassroots, community supported, self-propelling fan art. Unfortunately, this is extremely difficult for a brand to pull off, both ethically and aesthetically. Sony famously blew it with their infamous 2005 PlayStation Portable graffiti campaign, their faux street art, visually unclaimed by the brand itself, was physically and emotionally rejected from the very community they were trying to reach. The hazy lines of brand authenticity and consumer trust were breached, and Sony suffered.

The most recent victim of guerrilla marketing backlash was none other than the much loved indie-gone-mainstream band Arcade Fire. For their new album “Reflektor,” which is, incidentally very good, the band’s leader embarked on a self-declared “weird art project” to promote their 9/9/13 release. The “art” in question came in many forms, banners, posters, and most controversially, spray painted stencils. Though the band eventually claimed responsibility for the mysterious symbols popping up in urban spaces, they were originally quite cryptic and, in essence, vandalism.

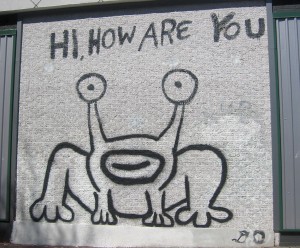

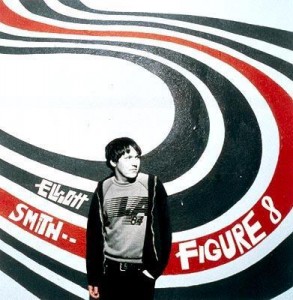

Graffiti and indie music have a long, trusted relationship. Within certain bounds, it’s cherished and celebrated amongst fans—Daniel Johnston’s “Hi. How are you?” frog (Austin, TX) and Elliot Smith’s Figure 8 mural (Silver Lake, CA) have even gone as far as becoming shrines to their late or struggling artists.

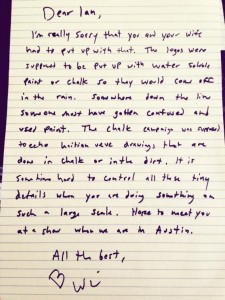

And though many thought the “Reflektor” campaign was ingenious, one particular man and his wife, whose small business was victim of the band’s “arty” vandalism felt otherwise. Used, and betrayed, in fact. And they would consider themselves fans of Arcade Fire. Ian Dille sums up the nuanced distinction quite nicely:

“If you’re a talented young artist who considers the urban environment your canvas, by all means, spray-paint a building. If you’ve got a radical social agenda and you think spray-painting property is the best way to convey your message? Go ahead. If you’re a gangbanger and you want to mark your territory, I can learn to live with that.

But if you’re an internationally renowned band that’s defacing public and private property for promotional purposes, maybe go back to the drawing board, and think some more about how you want to let people know about your music.”

It is worth noting that the band’s front man, Win Butler, publically and personally apologized, explaining that the paint in use was intended to be water soluble, the damage had already been done. Literally and figuratively.

Resources:

Banksy. (Director). Guetta, Thierry. (Producer). (2010). Exit through the gift shop [Motion picture]. United States: A Banksy Film.

CBC News. (2009). When ad campaigns go bad. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/when-ad-campaigns-go-bad-1.826689

Coulehan, Erin. (2013). Arcade Fire’s Win Butler sheds light on ‘Reflektor.’ Rollingstone Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/arcade-fires-win-butler-sheds-light-on-reflektor-20130911

Dille, Ian. (2013). My wife was vandalized by Arcade Fire. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2013/09/12/arcade_fire_graffiti_marketing_vandalism_or_both_relektor_ads_are_a_nuisance.html

Musgrove, Mike. (2005). What looks like graffiti could really be an ad. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/12/25/AR2005122500589_pf.html

Pelly, Jenn. (2013). Arcade Fire confirms Reflektor campaign is theirs. Pitchfork Music. Retrieved from http://pitchfork.com/news/52041-arcade-fire-finally-confirm-reflektor/

Singel, Ryan. (2005). Sony draws ire with PSP graffiti. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/culture/lifestyle/news/2005/12/69741